|

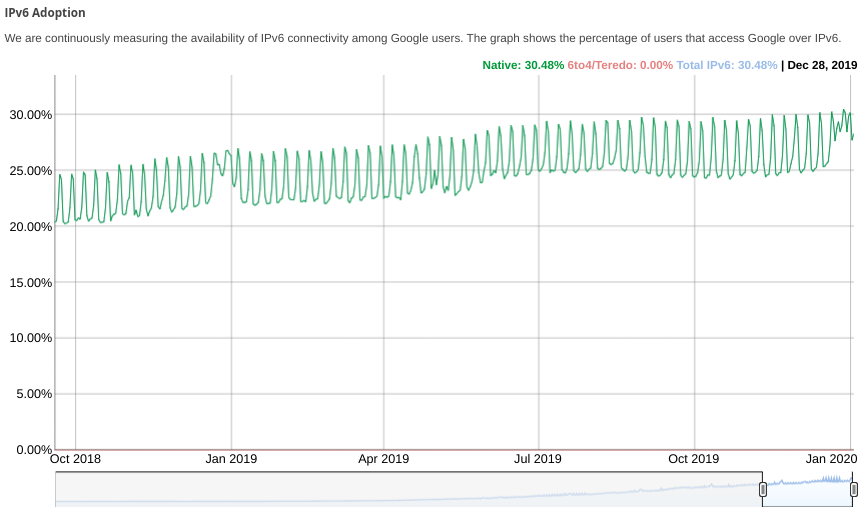

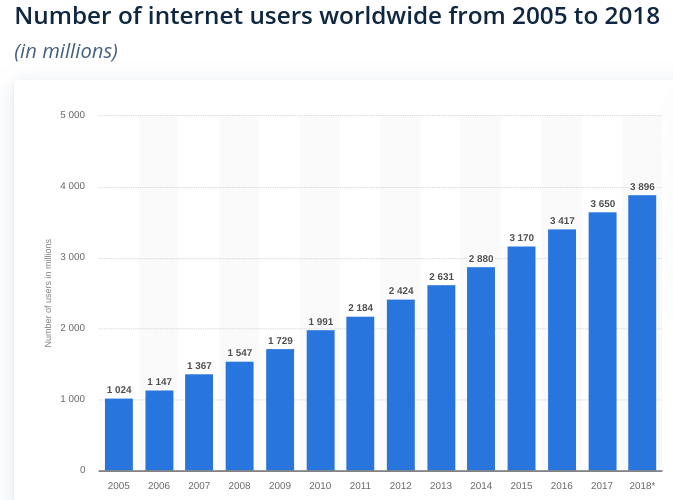

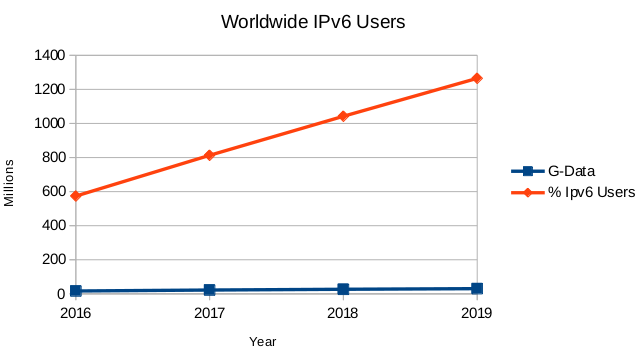

The year is 2020, IPv6 has been a standard for over 22 years. And amazingly enough, there are still networking products which aimed solidly at the IPv4 customer, such Ubiquity.

I bought the Ubiquity EdgeRouter X, thinking it would be a nice addition to my IPv6 Test network. Basically it is a five (5) port GigE router (with eth0-eth4). It had a wonderful specifications list, supporting many features I recognized, and some I even planned on using, like RIPng.

Basic Specs of the EdgerRouter X

The Ubiquity Spec sheet is impressive, including five GigE ports, and a 4 core MIPS CPU with 256 MB of RAM. Here’s some of the following of what the EdgeRouter X supports right out of the box.

| Feature | Protocol |

|---|---|

| Interface/Encapsulation | 802.1q VLAN PPPoE GRE IP in IP Bridging |

| Routing | Static Routes OSPF/OSPFv3 RIP/RIPng BGP (with IPv6 Support) |

| Services | DHCP/DHCPv6 Server DHCP/DHCPv6 Relay Dynamic DNS DNS Forwarding VRRP RADIUS Client Web Caching PPPoE Server |

| Management | Web UI CLI (SSH, Telnet) SNMP NetFlow LLDP NTP |

Lots of protocols to keep an old Bay Networks person, like myself, busy for some time.

EdgeRouter X and IPv6 Support

The EdgeRouter X is the bottom of the product line for Ubiquity. After all, it only costs $60 USD on Amazon. And it does have impressive IPv6 support. But the catch is that one must use the CLI to configure IPv6. The web interface is nearly totally devoid of IPv6 configuration and operational status.

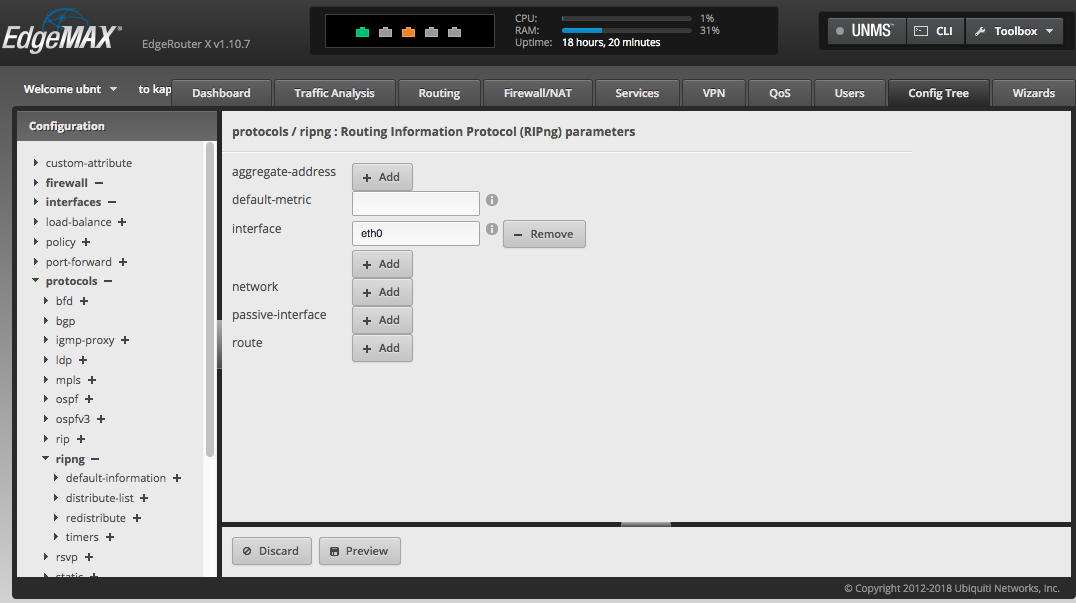

Having worked in product development, including software development, and CLI design, I can see many of the challenges the designers had with creating a cohesive interface. For example, do you add a router protocol (such as RIPng or OSPFv3) to a port, or do you add ports to the routing protocol? Ubiquity decided to split the difference, and add some config to the ports and other parts of the config to the routing protocol.

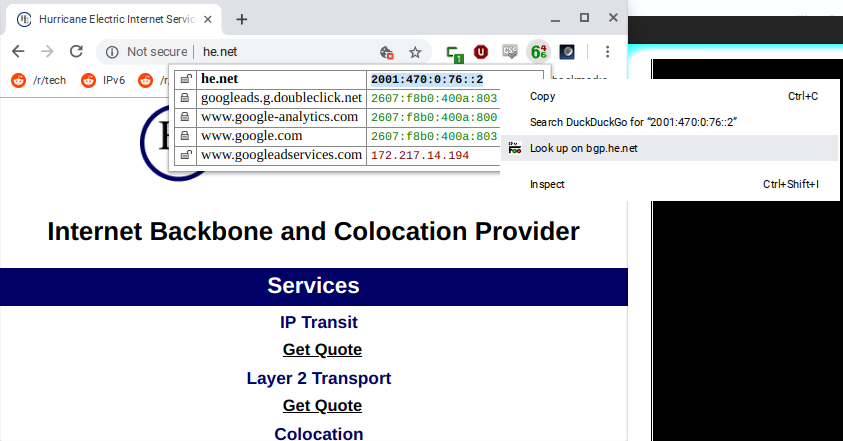

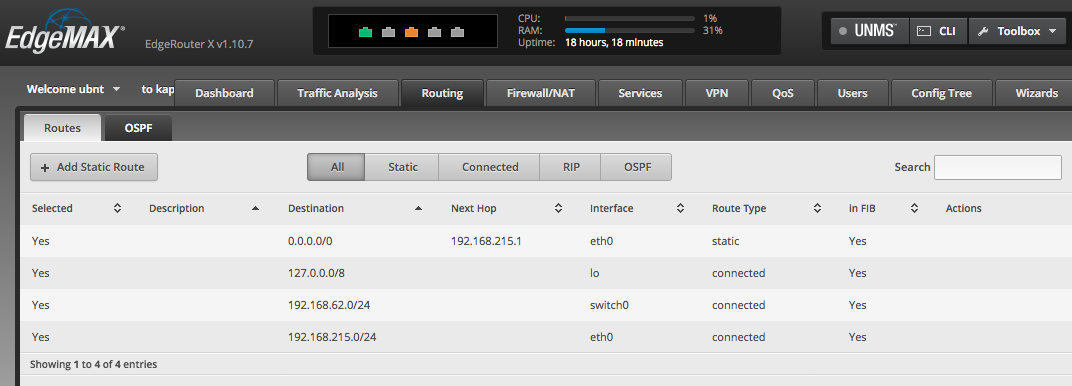

Little IPv6 seen in the GUI

Unfortunately, the Web Interface is lacking in IPv6 support. For example, here is the Routing tab. And this router has RIPng running (configured via CLI) with plenty of IPv6 routes.

To be fair to the Web GUI, there is a Configuration Tree in the GUI, that basically maps the CLI into a tree, where IPv6 protocols can be configured:

DHCPv6-PD

Although the CLI looks like it will support DHCPv6-PD, I was unable to find success attempting to configure a /60. I repeatedly got an unhelpful error “64 + 4 + 64 prefix too long” (which of course exceeds 128 bits of IPv6).

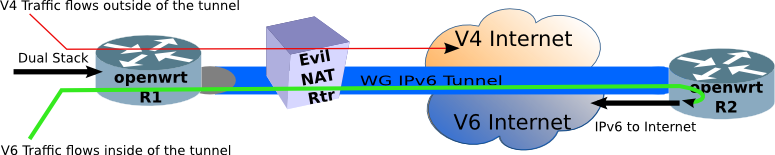

OpenWrt to the rescue

Although the dazzling list of supported protocols was enough for me to purchase the EdgeRouter X, the really nice part, is that the little capable router is also supported by OpenWrt, which does have excellent IPv6 support.

Typically the steps to upgrade a OpenWrt supported router is:

- Download the “factory” install image from the OpenWrt website to your laptop

- Log into the router, and find the software upgrade section (different for every router manufacturer)

- Upload/Upgrade the router with the OpenWrt software

- Log into the router, and enjoy OpenWrt

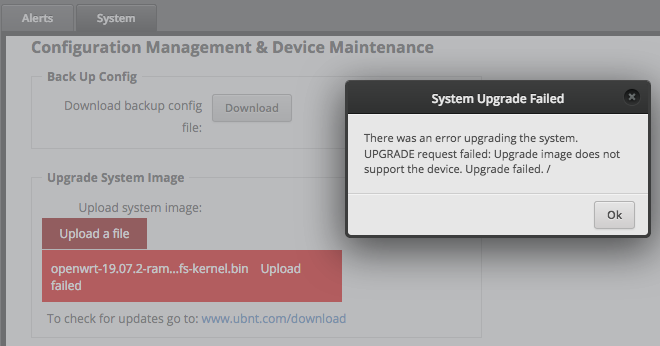

Upgrading the EdgeRouter X to OpenWrt was not quite as simple as other routers. Unfortunately Step 3 fails. The EdgeOS upgrade screen will not accept the latest OpenWrt “factory” install image.

Fortunately, the open source community has not only created steps, but an OpenWrt image which will be accepted by EdgeOS.

The Steps to upgrade the EdgeRouter X becomes:

- Download the interim tar file image from open source community to your laptop.

- Log into the router, and find the software upgrade section (Under System->Upgrade System Image)

- Upload/Upgrade the router with the interim OpenWrt software

Half way there

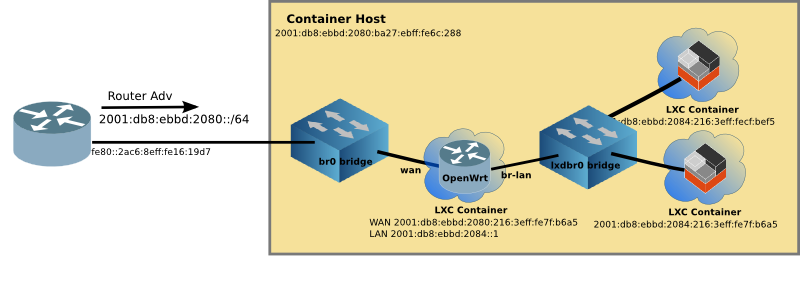

The router will reboot, and have a default address of 192.168.1.1 with no password (the default for OpenWrt), and no GUI. There is also a default ULA address, if you only have IPv6. The router will send an RA with a ULA* prefix, such as fd45:1373:e6bd::/48 The router will have the ::1 address. In my example, router address was fd45:1373:e6bd::1, which you can ssh to.

But that only gets a minimal OpenWrt snapshot running on the EdgeRouter X. In order to finish the upgrade, one has to download the v19.07 Upgrade image from OpenWrt to your laptop, then connect to one of the ethernet LAN ports (eth1-4), and scp it over to the router’s /tmp directory.

scp openwrt-19.07.2-ramips-mt7621-ubnt-erx-squashfs-sysupgrade.bin 'root@[fd45:1373:e6bd::1]/tmp/'

Log into the router via ssh using the IPv4 or IPv6 default address.

ssh root@fd45:1373:e6bd::1 #use your own ULA prefix here

cd /tmp

sysupgrade openwrt-19.07.2-ramips-mt7621-ubnt-erx-squashfs-sysupgrade.bin

As part of the sysupgrade, the ssh session will disconnect, and the router will reboot.

Log into the OpenWrt Web GUI

After the reboot, you should be able to log into the OpenWrt Web Interface. In my case, I put the IPv6 ULA into the location bar in the browser (yes, the square brackets are required for a raw IPv6 address).

http://[fd45:1373:e6bd::1]/

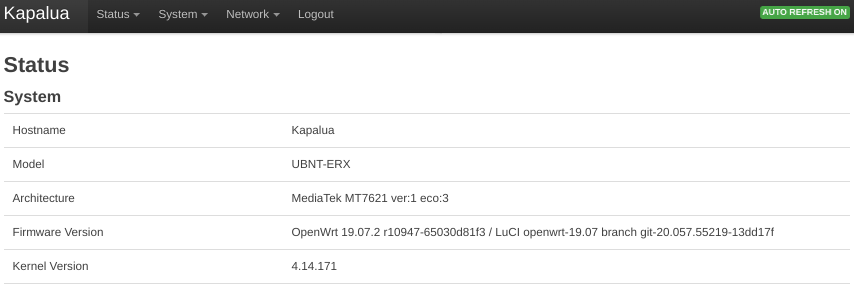

And you will see that OpenWrt reports that the hardware is a UBNT-ERX (short for Ubiquity EdgeRouter X)

Tthe first port of the router is the WAN port (eth0), and if connected to an upstream Dual-Stack network, you will see that the EdgeRouter X has picked up an IPv6 GUA, and automatically requested DHCPv6-PD, and allocated a /64 to the downstream LAN ports (four right-hand ports eth1-4).

Performance

The EdgeRouter X has NAT forwarding hardware acceleration. This is an IPv4-only feature, but certainly useful in Dual-Stack networks. Using OpenWrt and HW NAT Acceleration enabled, it has been measured to have a blazing forwarding capacity of 846 Mbit/sec average, faster than the original Ubiquity software.

The software-only throughput is a respectable 643 Mbit/sec with all four cores pulling hard.

If you have a high speed Internet connection, this little high performance router is for you.

Summary

OpenWrt has excellent IPv6 support in its Web GUI, with reasonable defaults for obtaining an IPv6 address, delegating a Prefix, and IPv6 firewall rules.

The EdgeRouter X is a high performance home router for a low price. And fortunately, there is a choice to have excellent IPv6 support via OpenWrt.

* ULA (IPv6 Unique Local Addresses) begins with ‘FD’ followed by randomized 40 bits. OpenWrt follows RFC 4193 and automatically creates a ULA at install time.

Article originally appeared on Makiki.ca